Chapter One – The Hospital

The Feldman Sanatorium for Chronic Pain and Other Brain Disorders hovered over me like a kestrel. I had a mental image of the building sprouting wings, swooping down, plucking me off the sidewalk, and carrying me away to a private spot where it could tear me to shreds in peace.

Stop it. I gave my head a small shake.

It didn’t pay to let my brain wander wherever it wanted these days. According to El, I’d been paranoid ever since I’d discovered a poltergeist was dogging my steps. He was right. Poltergeists have that effect on people.

“This is it,” El said cheerfully. Too cheerfully.

“Really?” I was hoping he’d put the wrong address into the GPS.

“Really.” He took my hand and gave me a gentle pull toward the entrance. “The inside is nicer than the outside.”

Good news. The interior couldn’t be more gloomy than this dull brown and black facade.

El must have been reading my mind. He was good at that. He said, “They probably had to paint it those colors, historical accuracy and all that.”

Color schemes aside, I wasn’t excited about this visit. I didn’t like hospitals, even new, white, bright shiny ones. Worse yet, we were going to visit El’s mother. Again, he read my mind.

“I really appreciate you coming to see Mom with me.” El climbed the porch and towed me after him. “I know you and she didn’t hit it off.”

Didn’t hit it off was an understatement. Eleanor Brown wasn’t subtle about the fact that she wanted me out of her son’s life.

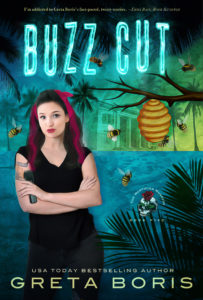

As we approached the house, I noted the top half of the front doors framed an elaborate stained glass image. A monk tending roses stood in the foreground. Bees buzzed around him. I wondered if the monk was the patron saint of something but had no time to ask. El opened a door and hurried inside, talking over his shoulder. “She asked to see you.”

I reluctantly followed. “Me?”

“Yes, you.” He gave my hand a squeeze. “She wants to thank you.”

I’d learned a few things after bumbling into yet another murderer’s path recently and suggested the medicine Eleanor was taking for her migraines might have been the cause of other disturbing symptoms she was experiencing. I was right. She stopped taking the pills and the symptoms went away. Unfortunately, the migraines returned. Hence the reason we were visiting her today at the Feldman Sanatorium.

“That’s not necessary,” I mumbled.

El strode to a tall, dark-wood reception desk situated near a curved staircase. A woman who took her fashion cues from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest stood behind it. Hair, sticky with spray, framed her unsmiling face. An outdated, starched-white uniform covered a spine that might have been constructed from titanium.

“We’re here to see Eleanor Brown.” El flashed a disarming smile at her, to no effect. Interesting. Most people melted in the warmth of that smile. Not her.

I gazed around as the nurse checked the computer. The room we occupied had graceful, curved lines. I saw an arched doorway just past the stairs, and through it, a series of rooms, each painted a different color. The first was gold, the next celery green, then maroon. Past that, all I could see were windows. Several other doorways opened off the reception area. I assumed they also led to their own lineup of rooms like the limbs of a starfish.

The sanatorium had been built by Rodger Humboldt, a wealthy landowner, back in the early 1900s. It was a ridiculously large home for a family of five, but that’s what the rich did with their money in those days. These days, too, I guess. Humans feel the need to dress to impress, which often extends to their abodes. Probably due to their lack of fur and feathers.

Nurse Ratched, whose name tag read Nadine, tightened her already tight lips as if what she was about to say was distasteful. “She’s in room 22.”

“Thank you.” El patted the desk and moved toward the stairs.

I gripped the handrail tightly as we ascended, something that had become second nature the past month. Stairs, balconies, cliffs, anyplace with altitude, were especially terrifying when a poltergeist was plaguing you. It only took one stumble, one invisible push, and poof. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust, as the funeral saying goes.

The second floor of the sanatorium wasn’t as well turned out as the first. The stairs led to a community room in which a TV blared Wheel of Fortune. One lone woman sat with her back to us on a nubby old couch, watching it. This room was round, similar to the entryway on the ground floor. It also had five hallways branching off it. El paused, glanced at each opening, and rubbed his chin.

“The one on the right?” I suggested.

He gave a half shrug and headed in that direction. There were six rooms in the right-hand hall, numbered one through six. We returned to the community room and tried the next hallway. If Feldman Sanatorium had a logical layout, the next series of rooms would’ve been seven through twelve, but they weren’t. They were numbered ten to sixteen, which made no sense at all. The next corridor held rooms seven through nine and seventeen through nineteen.

El’s brow furrowed in frustration when we returned to the community room. “Who numbered these things?”

“Maybe we should ask her where 22 is.” I nodded at the woman on the couch, still obviously engrossed in her game show.

“There are only five hallways,” he said. “Let’s not bother her.”

“Your mother’s room could be on the next floor.”

He opened his mouth to argue, but I’d stopped listening. I didn’t want to search the entire building for Eleanor, and it wasn’t because I was lazy. I felt like I was invading people’s privacy. The first hall we’d walked down, there’d been a white-haired woman laid out on her bed asleep, mouth wide open. Down the second, a man had sat in a window staring at the world with such a look of defeat on his face, I felt as if I’d seen into his soul, and it wasn’t pretty. Wandering around just didn’t seem right.

I stood behind the couch, so I couldn’t see the face of the woman who sat there. She might be dozing, but I decided to take a chance. “Excuse me,” I said.

She didn’t respond, so I raised my voice. “Excuse me.” Still no response. Maybe she was hard of hearing.

As I approached the couch, the scent of lilacs washed over me. Since I saw no flowers, I assumed it must be a favorite hand cream of the woman seated there. “Excuse me,” I said for a third time, but she didn’t turn. I placed a hand on her shoulder, brushing aside the salt and pepper hair that lay there in messy tangles, and gave her a gentle shake. That turned out to be a big mistake.